Case study: A tragedy in Metrowest

Let’s explore a case study involving a client I encountered in the past. This client was enthusiastic about buying a fixer-upper with the intention of making a profit, which they planned to use as a stepping stone toward purchasing their next home.

The clients had already bought their new home after completing renovations on the fixer-upper. Unfortunately, the renovated property was not selling, even in the extremely hot real estate market we were experiencing at the time. The financial advisor became concerned when the clients began withdrawing funds from their 401(k) to cover the mortgages on both properties.

The situation was dire: they owned an expensive new home, while their old, now-renovated home sat empty and unsold. Despite being in one of the hottest real estate markets we had seen, their property remained on the market, leaving them in a financial bind. This case prompts us to ask: how did they end up in this challenging situation?

Let’s use our analytical tools to understand the decisions that led to this particular outcome. The clients were a young couple living in Cambridge who decided to move to Metrowest to purchase a fixer-upper in the suburbs. Their goal was to take advantage of sweat equity to secure a larger down payment for their next home. They employed strategies they believed would help them make a profit.

Firstly, they chose a home that had been on the market for an extended period, thinking they could bid below the asking price and secure a bargain. They also decided to forgo using a real estate agent, believing they could select the home themselves and save on the commission fees.

The property they purchased was a Cape-style house with land abutting the Mass Pike, placing the highway directly in their backyard. When asked about this, they mentioned that the noise did not bother them. This is a common occurrence with city dwellers moving to the suburbs—they often overlook noises that might deter other buyers.

They bought the house during the summer, but it’s likely that in the winter, when the trees were bare, the headlights from the highway and the increased noise would have been much more noticeable. This oversight was a significant factor in their challenging situation.

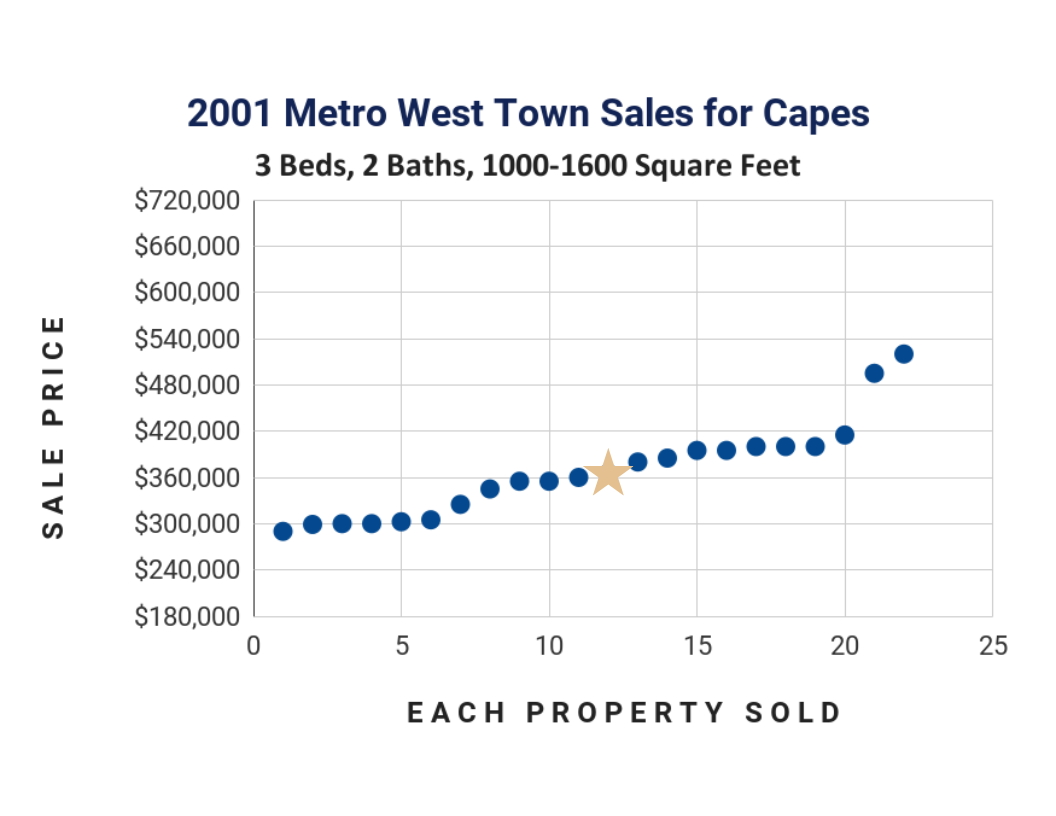

The clients purchased a house with a significant tragic flaw. They chose a home style that was less expensive than others in the town and made an offer on the property. Although they successfully bought the house at ten percent below the asking price, the property’s true value was even less than what they paid. This miscalculation set them up for failure from the start, as they aimed to profit from a fixer-upper by investing in a property with a tragic flaw. Additionally, the style of the home was not among the most desirable in the area, and they ended up overpaying initially. These are common mistakes that we frequently observe.

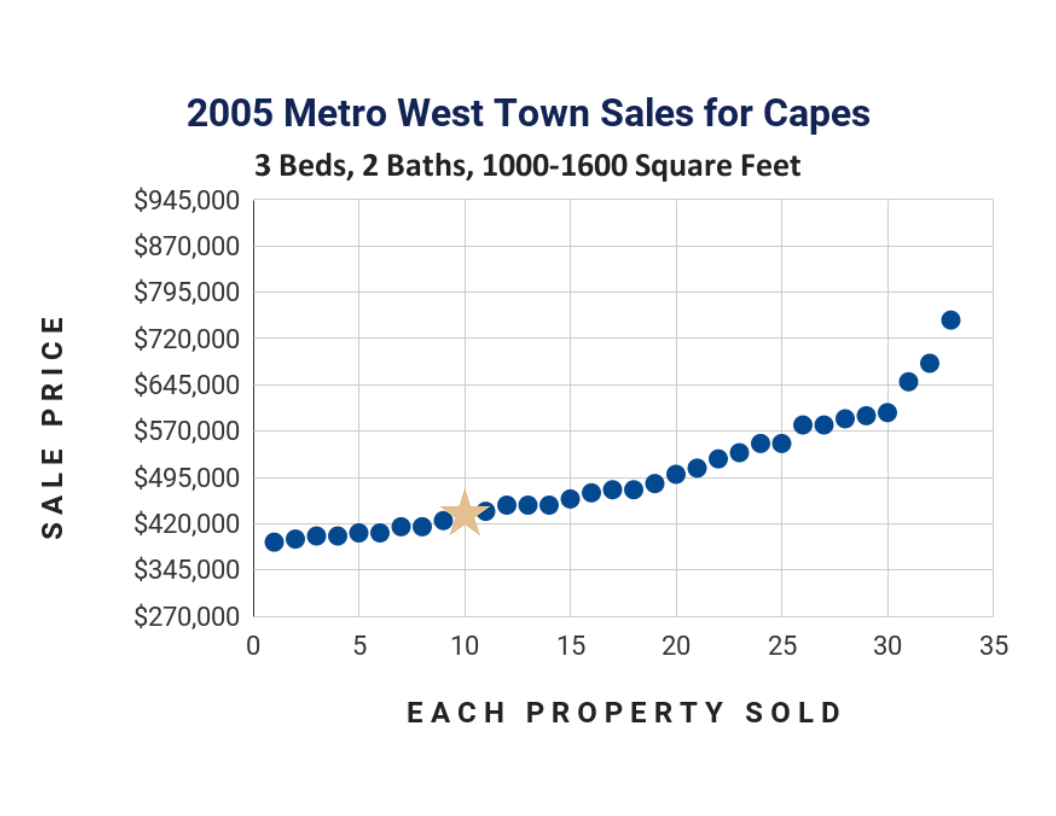

Over the next two years, the couple dedicated substantial sweat equity, money, and time to improve the house. They made several enhancements: painting the house, renovating the bathrooms, updating the kitchen, and installing a fence. The house turned out to be truly charming—adorable even. However, despite all these improvements, it remained as the “cutest tragically flawed house in town.” While it was visually appealing, it never became the best house in town due to its inherent limitations.

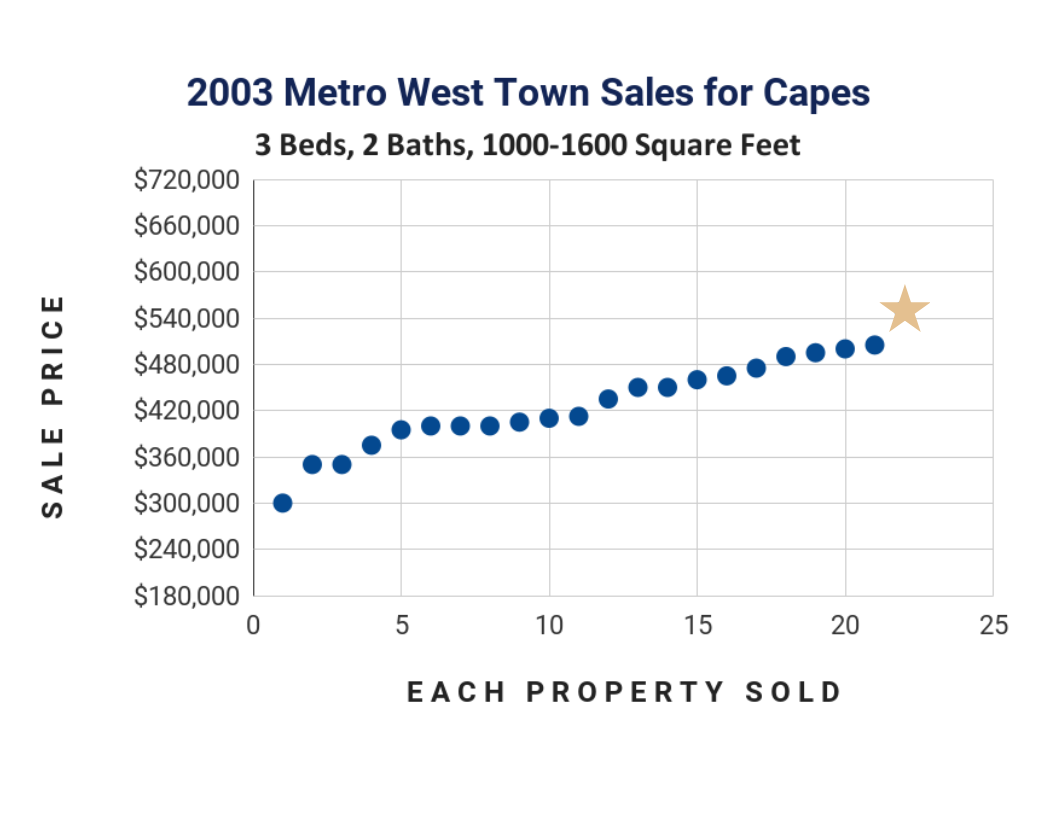

The clients decided to put their renovated house back on the market, calculating their selling price themselves to save on commission costs. They based their price on the initial amount they paid, which was already more than the house’s actual worth. Reading that the median home price in the area had increased by 30 percent, they added this percentage to their home’s value.

However, they failed to consider a critical detail: the median price increase was driven by the construction of new, significantly larger homes replacing the small Cape houses in the town. These new homes were priced around two million dollars, quadruple the size of their property, and brand new. The increase in median price did not reflect a rise in the value of the existing Cape houses like theirs.

The appropriate price for their house should have been at the lower inflection point—the highest possible value for the “cutest tragically flawed house in town.” When I first met them, their house had been on the market for quite some time. I managed to put the house under agreement at this price point, which was the best they could hope for given the circumstances.

However, they couldn’t keep that deal together and spent another year trying to sell the property. Ultimately, it sold for the same price a year later.

Despite being in an incredibly hot real estate market, they spent over five hundred days attempting to sell a house they had hoped would turn a profit. In the end, they lost about $50,000—approximately ten percent of the home’s value—due to carrying costs and the money invested in renovations.

In addition to their financial losses, they faced significant opportunity costs. If they had simply purchased a non-tragically flawed version of the same house, done no renovation work, and then put it back on the market in two years, they would have realized a substantial gain at a much lower cost.

If someone aims to flip a house or buy a fixer-upper to make a profit solely by improving its condition, they are unlikely to achieve success. The key to achieving a profit is typically by adding utility, such as bedrooms, bathrooms, or additional space. This increases the property value from one curve to a higher curve, creating the potential for a profitable sale.